Tommy James was a huge star when my mom was in high school. But his songs were everywhere when I was growing up in the 80s. Joan Jett was singing “Crimson and Clover”. The Rubinoos and Lene Lovich both did covers of “I Think We’re Alone Now”, but in 1987, everyone’s favorite mallrat Tiffany made the song a number one hit. And no school dance was complete without Billy Idol shouting “Mony Mony”. That song was ever-present – Billy actually charted the song twice. Apparently, my high school has banned the song from school dances these days due to a certain bit of traditional audience participation involving chanted profanities. I wouldn’t know anything about that.

Tommy James was a huge star when my mom was in high school. But his songs were everywhere when I was growing up in the 80s. Joan Jett was singing “Crimson and Clover”. The Rubinoos and Lene Lovich both did covers of “I Think We’re Alone Now”, but in 1987, everyone’s favorite mallrat Tiffany made the song a number one hit. And no school dance was complete without Billy Idol shouting “Mony Mony”. That song was ever-present – Billy actually charted the song twice. Apparently, my high school has banned the song from school dances these days due to a certain bit of traditional audience participation involving chanted profanities. I wouldn’t know anything about that.

While I knew all those songs were covers, I’m not sure I ever quite made the connection that they all came from the same source until I was in high school, and it wasn’t until I picked up a Rhino Records anthology of his music that I had the first inkling of just how fascinating and joyously inventive a talent the guy was, nor just how popular he had at one time been.

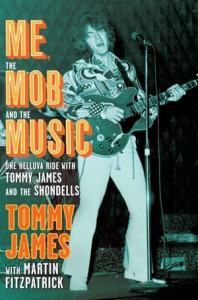

Born in 1947, Thomas Gregory Jackson was a prodigious little music geek from the Midwest, one who spent all his spare time (not to mention spare change) listening to music, hanging out at the record store, reading record industry trade magazines and fooling around with a ukulele. While his peers were collecting baseball cards and rattling off players’ statistics, Tommy was learning who was signed to what label, what songs were charting, and who wrote and produced them – and dreaming of seeing his own name on those little 7″ inch records with the big holes in the middle. In his new autobiography, Me, The Mob, and the Music, Tommy James likens the pleasure of 45 rpm records to candy. As a 45 lover myself, that comparison rung immediately true. And Tommy James put out some of the sweetest, most colorful chunks of audio candy in all of pop music. Some call his songs bubblegum; I like to think of them as Jolly Ranchers – intensely sweet, crystalline, and enduring.

Tommy James and the Shondells “Mony Mony” (1968)

Tommy was a working musician by his early teens, and he and his bandmates would cut the single that would launch Tommy to stardom when he was barely 16 years old. But “Hanky Panky” wasn’t an overnight hit. By the time some dj in Pittsburgh started spinning it in 1966, the band had long since broken up, Tommy and his high school girlfriend were married an expecting their first child, and staring down the reality of responsible adulthood. As it turned out, responsible adulthood would have to wait. For, like, a really long time. Me, The Mob, and the Music is billed as “one helluva ride”. That was what his boss at Roulette Records – the legendary (and infamous) Morris Levy – told Tommy he was in for the day he signed his first record deal.

Within five years of meeting Mr. Levy, the lanky teenager from Niles, Indiana would rack up an astounding 20 hit singles including classics like “Mirage”, “Do Something To Me”, “Crystal Blue Persuasion”, “Sweet Cherry Wine”, and “Draggin’ the Line”. He got to perform on the Ed Sullivan Show, and rub elbows with his musical heroes (who became his musical peers). And with later albums like Cellophane Symphony (whose title track is a 9-minute instrumental recorded entirely with a Moog synthesizer) he also became one of the very few artists to transcend an early (and well-earned) reputation as a teeny-bopper to make it with the hipper FM radio crowd in the late 60s. With his knack for inventive pop production, he ably straddled a line between artsy and commercial – his pop songs were rarely disposable, and his experiments were rarely indulgent. He approached songwriting and recording with a sense of purpose and drive. But most of all joy. His records are loaded with joy.

Tommy James “Sweet Cherry Wine”

But as with any good rock ‘n’ roll story, the Tommy James story isn’t all fame and glory. Me, the Mob, and the Music details the challenges unique to working for a guy like Morris Levy, whose almost certifiably sociopathic business sense was paired with a strong paternal protectiveness, and whose ties to the Genovese crime family in New York would eventually put Tommy James’s career (and his life) in danger. It’s also a story about addiction, recovery, failed relationships and family. Both mostly it’s about his music and his conflicted and financially abusive “father-son” relationship with the volatile and manipulative Morris Levy, which continued long after James severed professional ties with the man.

In fact, there’s very little in the book dealing with James’s “real” family. He checks in periodically on who he was dating or married to at various points in his career, but after the formative years, we don’t get much about what his parents thought of their only son’s stardom, or how it affected his relationships. Though James was a father at 17, he’s never a father in this book – he’s always “the kid” around the Roulette offices – and his son is only mentioned in passing. Maybe that’s another book. As it is, Me, the Mob, and the Music is as quick and engaging as any of Tommy James’s pop songs. It’s written in a very anecdotal style that makes it pretty breezy reading, and it offers a glimpse into the rise of a 60s superstar, the inner workings of Roulette, one of the iconic pop empires of its time, and the tragic downfall of its beloved tyrant emperor.

Tommy James “Go” (1990)