Saturday afternoon, I was busy doing something or other in the kitchen when my partner, browsing at his computer, asked rather non-urgently, “So, who’s Amy Winehouse?” “Why,” I asked him, “Is she dead?” “Yup,” he replied. The singer’s tragic but not terribly surprising death was the “duh” heard ‘round the world over the weekend. Even as authorities try to tamp out the rampant speculation over the cause of her demise, her signature tune – the one she’ll be most remembered for by our kids – was ringing like a grim YouTube joke that had finally found its punchline. As I saw in one poster’s bio line Saturday night: “They tried to make me go to rehab, and now I’m dead, dead, dead.”

And so the career of this strangely beautiful singer came to its depressingly predictable end. But not without one last stupid nod to the clichés of gone-too-soon rock stardom: Amy Winehouse is the latest dues-paid member to join the 27 Club, that legendary pantheon of self-destruction – Janis, Jimi, Jim, and most recently (albeit a full generation ago) Kurt – all reluctant “voices of their [respective] generation” who martyred themselves to the gods of image-licensing, who gave their lives to become black velvet posters to be won at county fair midway games.

But here’s the thing about the 27 Club: it’s a bullshit club. And in the case of Amy Winehouse, it confers a level of artistic legitimacy and importance to a career that had scarcely earned it.

It’s true, I’m no Amy Winehouse fan; but let’s be clear: I’m no hater either. While Winehouse had a distinctive image and delivery, the best thing about her 2006 breakout album “Back to Black” was its defiant sense of deep pop history, most evident in the Northern Soul revival production by Mark Ronson. It was a sound that stood in stark opposition to the Autotune-heavy radio fodder it shared the airwaves with.

All that said, Winehouse’s unique talent was not so much as a singer, but as a disaster in progress. She left a decidedly scant (and spotty) recorded legacy, and her live performances in recent years have ranged from harrowing to pathetic. Yes, a few of her songs may have gotten play on the radio, but what’s really fascinated us most about Winehouse (right or wrong) for as long as we’ve known her, has been her long, relatively fruitless march to an early grave.

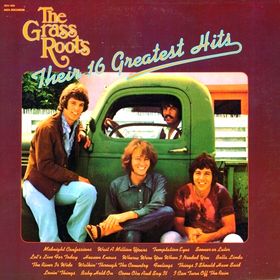

Rob Grill (in the cab of the truck) 1943-2011: My parents had this record when I was little and I played the hell out of it.

Leaving aside the fact that there have been only two new members of the 27 Club in my lifetime, why such reverence for 27, when surely, you can pick any age and find some arbitrarily linked contingent of musical greats who kicked the bucket there? Why not the 67 Club? Or the 57 Club, latest inductee Doug Fieger of The Knack, the guy behind “My Sharona”, a song that feels infinitely more joyful than anything Winehouse had on offer.

Why not the 47 Club with its cross-generational triumvirate of gay icons – Edith Piaf, Laura Branigan, and of course, Judy Garland? Or the 37 Club, home of the tragic male sex-symbol who died (often violently) at the cusp of middle age: Sal Mineo, Bobby Darin, Michael Hutchence.

Why even bother with the number 7? How about the 32 Club for dead rock drummers like Keith Moon, John Bonham, and, y’know, Karen Carpenter. Or the 40 Club for John Lennon, John Coltrane, and Johnny Thunders; the 50 Club for dead punk rockers Joe Strummer and Dee Dee Ramone (Joey just missed it). And speaking of just missing it, what about those icons of the 26 Club? Baby Huey? Gram Parsons? Nick Drake? What’s so magical about the number 27? Nothing. It’s bullshit.

Now, take, for instance, the death a couple weeks ago of singer Rob Grill, at the age of 67, following a head injury. Grill was the lead singer of The Grass Roots, a band whose songs became a staple of AM radio from 1965 to 1975, right around the time the so-called 27 Club was first “established”. True enough, Grill was more singer than songwriter. The Grass Roots were the very definition of a singles group, and his band’s longtime producer Steve Barri was largely responsible for the group’s success. But it’s Grill’s voice you hear on more than 20 great Top 40 hits – songs like “Let’s Live for Today” and “I’d Wait a Million Years” that did as much to define their era as those by his contemporaries, the 27 Club’s charter members.

I grew up listening to my parents’ Grass Roots records right alongside my own Duran Duran and Culture Club 45s, and I’ve spent countless hours singing along with Grill: in my bedroom growing up, in my Grunge-era college dorm room, and in my car this morning. His voice was not especially distinctive. But he looked good. And his singing was straightforward, and at its best, conveyed a powerful sense of urgency and purpose. He lived long enough to see his band’s rise and fall, make a few modest comeback attempts, and to tour the oldies circuit. As an artist Rob Grill was never terribly fascinating. As a musician and as a human being, he probably accomplished more than Amy Winehouse ever aspired to. But his death warrants only a small blurb in the latest issue of Rolling Stone. R.I.P., Rob Grill, distinguished member of the 67 Club.

At 27 years old, Amy Winehouse coulda been a contender. Then again, after 5 years and no follow-up record, it’s conceivable that, had she lived to join the 67 Club, she coulda been merely somebody who had once, briefly, been somebody. Not unlike a lot of the now anonymous, aging and/or dead girl group singers she herself revered as signified by that signature beehive. That, more than anything – more than any of her records, which, in their best moments do hint at some kind of forever unrealized greatness – will be her legacy. Forget the 27 Club. It’s so 40 years ago.