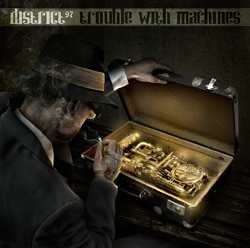

Artist: District 97

Album: Trouble with Machines

District 97 are a Chicago band of four varyingly dorky-looking male rock musicians, all quite skilled; a not-at-all-dorky-looking woman named Leslie Hunt who joined the band after being a top-10 finalist on American Idol; and a cellist, Katinka Kleijn, talented enough to do solos for the  Chicago Symphony Orchestra. That lineup concept is why I tried them out in the first place. Say what you like about American Idol (in my case, “I’ve never watched it”), Kelly Clarkson made it clear early on that it’s a fine machine for the discovery of singing talent, stretchable beyond any musics that the show itself — from what I’m told — would demonstrate. For example! While I’ve ranked District 97’s Trouble with Machines slightly above Rush’s Clockwork Angels, what I’d emphasize is that they’re comparable. If you’re a fan of one, I think there’s a good 75% chance you could end up a fan of the other.

Chicago Symphony Orchestra. That lineup concept is why I tried them out in the first place. Say what you like about American Idol (in my case, “I’ve never watched it”), Kelly Clarkson made it clear early on that it’s a fine machine for the discovery of singing talent, stretchable beyond any musics that the show itself — from what I’m told — would demonstrate. For example! While I’ve ranked District 97’s Trouble with Machines slightly above Rush’s Clockwork Angels, what I’d emphasize is that they’re comparable. If you’re a fan of one, I think there’s a good 75% chance you could end up a fan of the other.

On a broad level, both albums are full of ambitious, multi-segmented, quasi-metal songs that rock out. District 97 even attempted an album-long story on their excellent 2010 debut Hybrid Child, although this time they restrict that impulse to the individual 10-minute story-songs the Perfect Young Man and the Thief. Micro-level similarities include near-identical drumming styles (drummer Jonathan Schang is even District 97‘s primary composer); bass to some extent (Patrick Mulcahy often matches Geddy Lee’s more aggressive tones, though at other times he’ll essay a Metallica chug, spacious and staccato math-rock, or punk-pop simplicity, instead of Lee’s funk or melodic leads); and some tuneful heavy-metal guitar solos (Jim Tashijian’s being shinier and more ’80s rapid-fire than Alex Lifeson’s). Both albums also are full of angular vocal melodies, although where Lee’s tunes on Clockwork Angels often felt unfinished and wandering to me, Hunt’s on Trouble with Machines are clearly odd on purpose, making precision leaps over chasms. She’s got more than enough charisma to sell them, at least to me.

Rob Clearfield’s keyboards have a flashiness, and a hookiness, that fits far better with the Rush (or Yes) of thirty years ago. So, too, do the frequent time-signature switches here. Back and Forth and the Perfect Young Man feel especially like hybrids of Rush old and new. The lean, slippery Who Cares? is its own beast: Tashijian’s limber, non-distorted guitar reminds me of his acoustic-based side band Treehouse, and Hunt’s singing is at points more yearning, more bitter, and more taunting than progressive rock in general is known for. Open Your Eyes, the single in 4/4 time, has a catchy Pat Benatar-like directness (although still a fairly unusual melody). The Actual Color — melodically and rhythmically the bizarrest song on Trouble with Machines — has nonetheless a dramatic and emotional heft that reminds me of Queen’s later records. Read Your Mind opens with a nifty, elegant minute-long demonstration of various tricks cellist Kleijn learned in conservatory; the song as a whole is at once the most Clockwork Angels-like track here, and the one most influenced, in its slower, more drawn-out moments, by chamber music and by the synth-jazz-pop early-80s works of Joe Jackson (Steppin’ Out) and Donald Fagen (New Frontier). Final track the Thief makes me admit I’m being silly not having brought up Dream Theater before. It’s song-like enough and often gentle enough to be on Images and Words, but with group-playing segments fiery and jaw-dropping enough for … how did Dream Theater let Rush beat them to the song title an Exercise in Self-Indulgence anyway? Don’t give me that “They weren’t born in time” excuse; temporal immobility is for losers. Anyway, there’s enough song on the Thief that the instrumental parts enhance it rather than upstage it.

Like those other bands, District 97 try to sing about lives well or poorly led. Unlike those other bands, District 97 do so by centering on personal relationships: flirtations, cliques, seductions, breakups, encouragements, marriages, children, illnesses. In the broader context of pop music that’s conservative; in progressive rock, it’s almost radical. Right now the lyrics need work, I’d say: they sustain a narrative *or* scatter a few good lines, but not both. This album is high on my list for how great it sounds. There’s potential for something deeper next time. I’ll be listening.

– Brian Block

To see the rest of our favorites, visit our Favorite Albums of 2012 page!