Artist: Robyn Hitchcock

Album: Love from London

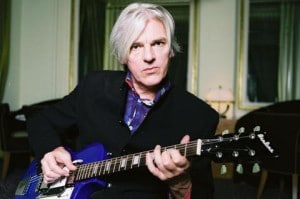

As I wrote to introduce my review of Robyn Hitchcock‘s 1999 masterpiece Jewels for Sophia (which is a more impassioned, therefore better, review than this one will be), “Robyn Hitchcock sings with an educated, amused English voice, and he’s  uniformly regarded as quirky”. For his fans who’ve kept up-to-date, my review of Love from London can be very short: it’s in the same style, and of the same quality, as Goodnight Oslo and Tromso, Kaptein immediately before it. This means, notably, that it’s *not* particularly quirky: as he’s approached old age, he’s begun to describe scenes, people, and feelings directly rather than chattering evasively around them. His voice is also much rougher than it was even a few years ago, which can make it sound tireder or more longing or sultrier (though, if we’re honest, “tired” wins out most often).

uniformly regarded as quirky”. For his fans who’ve kept up-to-date, my review of Love from London can be very short: it’s in the same style, and of the same quality, as Goodnight Oslo and Tromso, Kaptein immediately before it. This means, notably, that it’s *not* particularly quirky: as he’s approached old age, he’s begun to describe scenes, people, and feelings directly rather than chattering evasively around them. His voice is also much rougher than it was even a few years ago, which can make it sound tireder or more longing or sultrier (though, if we’re honest, “tired” wins out most often).

Nonetheless, he is clearly the same singer and songwriter. By my standards Love from London is a middling-quality Hitchcock album, which equates to a very good album in general: tuneful, well-sung, tastefully-arranged songs carrying forward a standard of pop music from the era of the Byrds, Beatles, Hollies, and Zombies, unconcerned that pop music today has gone elsewhere. (A couple songs are weirder, which I’ll get back to.)

Harry’s Song, sung over circling, echoey minor-key piano, sets a solemn mood from the start. The lyrics aren’t online, so I’ll transcribe a couple verses to get you a feel for how he puts ideas together: “Nothing answers like the ocean, to the albatross that punctuates the sky. Pterodactyls used to hang there, silhouetted high above the broken sea. Nothing wants you like tomorrow; only me./ Click on me to find my footsteps, till they vanish in the ever-loving green. Nothing tortures you like how it could have been./ But I don’t know anything about you, anymore./ She’s in solitary confinement. You’re just lonely, but you know your way around.” Be Still, pushed along by strums and a simple drumbeat, later joined by eighth-note cello and other bowed strings, is also about trying to know the mind of another: “I wonder what she’s thinking as she’s sitting next to me, although her eyes are open and she’s staring at the sea. She’s lost in contemplation as her hair hangs to the ground. I wonder is she praying, is she making any sound?/ What is swimming through her mind, as she sits alone? As beautiful as silence and as quiet as a stone. I wonder where she’s heading when she goes back into town. Who does she relate to, when she puts her money down?/ Be still. Let the darkness fall upon you.”

Stupefied, a slow-to-midtempo song that feels a bit jauntier from its quick tabla-like percussion, nods towards a whimsical opening (“Ain’t no money on the ceiling/ ain’t no ceiling on the floor”) before immediately rhyming it with “Got that terrifying feeling you don’t love me anymore”. The waltz-time My Rain, with almost Middle Eastern electric guitar and violin, and haunting, sighing backup vocals,  has his singing voice in low shredded wreckage as he asks “My rain it falls through dark mossy walls. Do you know where it’s been? My rain it comes through dark and purple lungs. Do you know what I’m in?” The pattern I’m seeing is that Love from London‘s songs are driven by the impossible challenge of truly understanding another human being, even one you see and care for every day. Arguably, these are not topics best served by Robyn Hitchcock‘s old strategy of strewing deep feelings and thoughts in a distracting mass of references to Mongol conquerers, Dirty Harry sequels, and obscure types of cheese. Which I respect — although my strategy has been to surround myself with friends who are preposterously blunt and outspoken about everything, thus allowing me to understand them fine. And then, after giving them regular reinforcements of whatever they need, I go think about microscopic camel superheroes fighting evil in bloodstreams across America, instead.

has his singing voice in low shredded wreckage as he asks “My rain it falls through dark mossy walls. Do you know where it’s been? My rain it comes through dark and purple lungs. Do you know what I’m in?” The pattern I’m seeing is that Love from London‘s songs are driven by the impossible challenge of truly understanding another human being, even one you see and care for every day. Arguably, these are not topics best served by Robyn Hitchcock‘s old strategy of strewing deep feelings and thoughts in a distracting mass of references to Mongol conquerers, Dirty Harry sequels, and obscure types of cheese. Which I respect — although my strategy has been to surround myself with friends who are preposterously blunt and outspoken about everything, thus allowing me to understand them fine. And then, after giving them regular reinforcements of whatever they need, I go think about microscopic camel superheroes fighting evil in bloodstreams across America, instead.

While none of Love from London is goofy, only 70% of it is tasteful and pretty. I Love You is a wild card, arrangement-wise: an intense and danceable assemblage of drones and sonic wobbles and half-rapped singing and slow firm drums and shiny glinting shards of guitar that reminds me of Stone Roses or Happy Mondays, or a sexier, giddier rewrite of Tomorrow Never Knows. Devil on a String is like the dirty rock’n’roll of ZZ Top or George Thorogood & the Destroyers, processed into psychedelic semi-abstraction and placed over fast, suspiciously foreign percussion elements like maracas. And the riff-heavy, tremolo-riddled Fix You, while just as personal (“Now that you’re broke, who’s gonna fix you up?”) lets in a broader world: “They make you redundant, then blame you for being a slacker/ while the financial backer is taking a call with a strawberry mousse”.

“They let you fall in the marketplace”, Fix You announces angrily, and one recourse for that (as Hitchcock would agree) is government. But the other is personal connection. Both can be tricky to get right. And obviously we don’t want to just let people hang around being broken. I can see, then, why Robyn Hitchcock decided to focus his words more sharply on task.

– Brian Block

To see the rest of our favorites, visit our Favorite Albums of 2013 page!