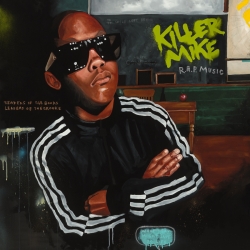

Artist: Killer Mike

Album: R.A.P. Music

Mr. Michael Render does not believe the term “rap” *is* an acronym for “Rebellious African Peoples”: he believes it should be. R.A.P. Music, produced by robot-apocalypse meister Jaime “El-P” Meline, does its best to sound like rebellion in progress. Beats range from firm to concussive;  synth melodies burble and warble like distant alarms, or buzz and gurgle like hungry monster wasps, or drift like machines humming to themselves while they recharge for their next burst of menace. There’s guest singers sometimes, with pretty melodies, but that just shows there’s a base of popular support out there, while Killer Mike‘s voice has the depth and forceful character of Public Enemy’s Chuck D, more speed, and the precise articulation of a man who knows how to wield the King’s English in the cause of regicide. At least when he so chooses; it’s not often that he sustains a verse without the word “shit”. But he’s impressive when he does.

synth melodies burble and warble like distant alarms, or buzz and gurgle like hungry monster wasps, or drift like machines humming to themselves while they recharge for their next burst of menace. There’s guest singers sometimes, with pretty melodies, but that just shows there’s a base of popular support out there, while Killer Mike‘s voice has the depth and forceful character of Public Enemy’s Chuck D, more speed, and the precise articulation of a man who knows how to wield the King’s English in the cause of regicide. At least when he so chooses; it’s not often that he sustains a verse without the word “shit”. But he’s impressive when he does.

A digression that maybe isn’t one. I feel like the only way to write this review honestly is to admit an unlikeable personal flaw: I’m kind of a prude. No, not about sex! I’m enthusiastically pro-sexual pleasure: mine, hopefully yours, anyone’s who doesn’t get theirs by treating people badly. Sexism, though, raises my hackles at once; so do violence and cruelty, all of which I think I’m right about. I’m also immediately bothered, to a muted extent, by things I know are absolutely none of my business, things that some of my favorite people enjoy: drunkenness, recreational drug use, boasting (unless it’s a fun burst of surprised enthusiasm), and large-scale swearing (unless it’s creative). These are, collectively, a large obstacle to hip-hop fandom — although as the two higher-ranking hip-hop albums remaining in the countdown will show, not a total one.

Those of you who are non-prudes probably mis-understand the phenomenon. Prudes are usually shown in the media as people who are lying about what they enjoy or think is funny; people who are refusing on purpose to have fun. My experience says otherwise; I was 5 years old and usually thought Garfield comics were the funniest thing in the world, but already that cat’s treatment of Nermal and Odie just made me sad. This is who I am. *I don’t have a choice* about wincing when R.A.P. Music‘s eloquent devotional to the power of music settles on, as its highest praise, “the opposite of bullshit”. I don’t have a choice about my disappointment when Untitled‘s awkward but affecting salutes to motherhood, and the mysteries of human potential, turns into a tribute to marijuana, then a boast that he’ll kill anyone coming to take him down. I can’t help disliking a chorus like Southern Fried‘s “Ain’t I one-hundred player for sure? Ain’t I slick ’bout my pimp game and just might mack on your ho?”, even as I admire the long-held organ chords and seductive almost-melodic dual vocals that deliver them.

I do have the choice — the easy and obvious choice — of ignoring entire giant swaths of American culture so as not to rouse my own disapproval. But that doesn’t sit right with me either. R.A.P. Music exemplifies the things hip-hop does better than any other genre. Autobiography, for one; love of family, for two; awareness of community and of unacceptable poverty, for three and four. Willie Burke Sherwood, for example, covers all four: it’s Killer Mike‘s plainly-titled tribute to the grandfather who raised him, to the books that influenced him even as he got mocked for reading books, and to childhood friends who were shot. A chorus like “This is for all the dads and the granddads/ and the little homies that ain’t never had dads… For every man that’s ever had to man up/ if that’s you, let me see you put your hand up” would sound totally out-of-place in indie-pop or progressive rock or shoegazer, but fits normally on a rap album, a song or three away from cheap ghetto pick-up lines.

Awareness of roots, for five. The title track is a lengthy boast about his and El-P’s skills, but it’s in the form of felt obligation — “What I say might save a life, what I speak might save the street” — and it’s also a lengthy namecheck of his musical loves, the “Closest I’ve ever come to seeing or feeling God”. When he says “This is sanctified sex, this is player pentecostal/ This is church: front, pew, amen, pulpit”, he’s talking about his own music (and a player lifestyle I wouldn’t endorse without knowing the women’s sides of the stories), but also the music others gave to him. Storytelling ambivalence, for six. Ghetto Gospel‘s narrator, accounting his drug-trade career, is viciously blunt with lines like “My mamma took me to the root lady to read my palm/ She puts beads on my neck saying they protecting me from harm/ But fuck this old witch, I went and got a gun”. But the narrator loves his mamma, and the proto-gospel tinges on the chorus “Oh Lord, Jesus, glory” don’t feel like cheap irony. Jo-Jo’s Chillin’ is a neutral tale of pure evil — a babydaddy fleeing his family and the law across state lines, bribing a guard, viciously abusing two women, and getting away with it — and I don’t doubt that it will be taken by listeners as glorification: I wish it wasn’t on the disc, despite its pleasant, stylishly listenable flow. But I’m not certain it’s supposed to be approving; it’s possible Killer Mike considers it as obvious a bleak character study as Jim Thompson’s “the Killer Inside Me”. Which, if it weren’t for all the rest of hip-hop, it might work as.

Awareness of roots, for five. The title track is a lengthy boast about his and El-P’s skills, but it’s in the form of felt obligation — “What I say might save a life, what I speak might save the street” — and it’s also a lengthy namecheck of his musical loves, the “Closest I’ve ever come to seeing or feeling God”. When he says “This is sanctified sex, this is player pentecostal/ This is church: front, pew, amen, pulpit”, he’s talking about his own music (and a player lifestyle I wouldn’t endorse without knowing the women’s sides of the stories), but also the music others gave to him. Storytelling ambivalence, for six. Ghetto Gospel‘s narrator, accounting his drug-trade career, is viciously blunt with lines like “My mamma took me to the root lady to read my palm/ She puts beads on my neck saying they protecting me from harm/ But fuck this old witch, I went and got a gun”. But the narrator loves his mamma, and the proto-gospel tinges on the chorus “Oh Lord, Jesus, glory” don’t feel like cheap irony. Jo-Jo’s Chillin’ is a neutral tale of pure evil — a babydaddy fleeing his family and the law across state lines, bribing a guard, viciously abusing two women, and getting away with it — and I don’t doubt that it will be taken by listeners as glorification: I wish it wasn’t on the disc, despite its pleasant, stylishly listenable flow. But I’m not certain it’s supposed to be approving; it’s possible Killer Mike considers it as obvious a bleak character study as Jim Thompson’s “the Killer Inside Me”. Which, if it weren’t for all the rest of hip-hop, it might work as.

It leads, after all, into Reagan, a bleak soundscape of drones and oscillations, a song opposed to ruthless brutality. As Tris McCall noted, it’s smart enough to explain the role of privately-owned prisons and the drug war in replacing the free labor lost to slavery, and dumb enough to call Reagan “an actor, not at all a factor, just an employee of the country’s real masters”, and also imply that he’s the antiChrist, as if the two were compatible. Hip-hop’s seventh special strength as a genre, that I’m thinking of today, is that it’s incendiary. This isn’t necessarily a plus. “Fuck the police” (a literal quote from Don’t Die), interspersed with threats to spree-kill said cops, is a pretty stupid response to the real problems of racial profiling, abusive illegal searches, and prison labor. Butane‘s call for revolution so that all you listeners can be as absurdly rich and royal and preternaturally cool as Michael Render is, um, not a realistic revolutionary goal. I get that.

But it’s something. No one this side of Fox News expects even as powerful a rap voice as Killer Mike‘s to translate directly into action: he’s starting a conversation, making nifty sounds in the process. Bart Simpson once tried to start a collective action with [paraphrased from memory] “I don’t promise success. I don’t promise victory”. As his collaborators started to wander away, he yelled “Okay! I promise success! I promise victory!”. It seems to work better.

– Brian Block

To see the rest of our favorites, visit our Favorite Albums of 2012 page!